We had an interview with graphic designer Wim Vandersleyen on the impact of logos, the creation of visual identity and about the B®ANDIT Logo Sessions

Wim Vandersleyen, founder of the eponymous graphic design agency (1999), is a designer pur sang. (website / instagram)

Observation is his second nature: from stickers and doorbells to the signage in the streets, nothing escapes his eye. He collects, draws and designs. He builds up and then breaks down again. He structures neatly but then disturbs that perfection just a tiny bit. Wim has no lack of ideas. On the contrary, he brings various visual elements together in fascinating ways. They are presented to the outside world in many different formats. The exhibition 'The B®ANDIT Logo Sessions' is just one of them.

Wim, what can we expect from your exhibition?

The B®ANDIT Logo Sessions' is the realisation of an idea I've been playing with for 15 years. The starting point is well-known logos that are part of our collective memory. To each of us, they are all familiar logos but have a personal connection as well. The connection we make with certain brands and the way they are woven into our memories is extremely fascinating. Without realising it, a logo can take us back to our childhood, be it in the form of a vague nostalgic feeling or in the shape of an actual event. Think of the blue or brown jars of Inex milk from which we drank our milk or chocolate milk at school. Or the Club Med logo, which for many is undoubtedly linked to a specific holiday.

When I reflect, the first logo that comes to mind is that of Kodak. This immediately takes me back to the many summers in the south of France that were captured on many rolls of film.

You are certainly not alone. Kodak has developed its branding in a very clever way. Their logo is woven into everyone's life and there really is such a thing as 'the Kodak moment'. Another interesting element is seeing logos in photos from our childhood. For example, I was a very sporty boy who spent half of my time playing in the street and outside playing football in my Adidas tracksuit. On most of the photos you can see that emblem on my clothing. When Adidas changed their original trefoil logo, I was really upset.

On the prints shown during 'The B®ANDIT Logo Sessions', you work with existing logos. Do you also create your own logos?

Certainly. And not just logos. The identity of a company, of a brand, also depends on the use of colour and form, the font, the positioning of text and illustrations. The creation of that whole is a fascinating but delicate process. A company or brand has often thought a long time about their personality and then it is up to me to give it a face. Usually, I know pretty quickly how that personality can be translated. However, the road towards it is often one with many bends and psychological manoeuvres until the moment one can identify with the end result.

From the very beginning, you helped create the visual DNA of Yugen Kombucha. How has that process been so far?

The first step was to listen to what Yugen means to the founders. Yugen is a Japanese word and stands for an overwhelming experience, often in nature, to which you cannot immediately put words. The image of this drink is linked to this: fresh, mysterious and a tad exotic. There is also the association with ecological awareness and the uniqueness in each of us.

I started with the front of the bottles and cans: the piece with the central text. For this, I found inspiration in the Japanese visual culture, among other things. As I often do, I make a comparative study of the way people in other countries and cultures use colours, shapes or fonts. Coffee bean bags are a good example of this.

By putting together the designs from different countries, you arrive at a kind of common denominator. For Yugen, more than 50 Japanese typographic compositions were compared in order to filter out a new one. After that, it was millimetre work. I made at least 100 different versions of the front, until the proportions were completely right.

The creation of the 'Yugen college font' completed the whole.

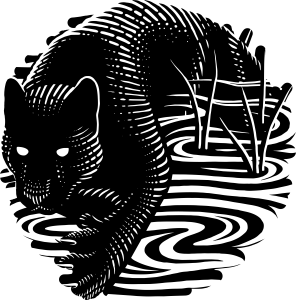

In addition to the front, the back of each Yugen flavour features different illustrations.

Because the front side is so neutral, the back side lends itself perfectly to a combination with the specific styles of different illustrators. Each flavour is linked to a different illustrator and corresponding circular drawing. The illustrator is given carte blanche, except for a rough definition of what Yugen stands for. The illustrators' own writing is thus preserved. The result is a very personal interpretation, which gives each can and bottle its own character.

It is striking how most of the illustrations are not immediately 'readable'. One discovers more different (natural) elements in them than a first glance would suggest.

Indeed. It is true that the drawings are in a sense layered. In that respect, one can notice a parallel with the word Yugen: an experience that cannot be grasped immediately. The illustrations are not crystal clear, but that is what makes them fascinating. Something that is not immediately clear or deviates just a little from the whole creates an end result that one wants to understand. Or in other words: something you want to keep looking at. For example, I have a strong fascination for Swiss typography, where the underlying basic grid is tangibly present. That leads to a clear whole, but it only becomes fascinating when something deviates from that scheme.

If you put 24 spheres in a grid and move one of them by half a centimetre, you get an image that is not quite right. Our brain registers this and searches for this deviation. This is the barb that makes people search unconsciously and, in the end, remember a message. As a graphic designer, you don't just create a message, you also think about how people see it and how they pick it up.

How do you keep the balance between the message the other person wants to convey and your own individuality as a designer?

This is done in various ways. For example, through exhibitions such as 'The B®ANDIT Logo Sessions'. By expressing my own ideas, space is freed up in my head for new ideas. I also draw a lot. I keep track of all the sketches, lines and illustrations that spontaneously appear on paper. Over the years, I have created an archive of hundreds of my own designs. A personal equivalent of stock photography, so to speak. When an assignment presents itself, I can call on this image library. It allows me to work partly spontaneously and to remain open to the unexpected.

What importance do you attach to the unexpected? Does it also play a role in your daily life?

Certainly, as a graphic designer you never run on automatic pilot. My colleague Kris Demey once compared it to a trip through the swamp. An apt metaphor. You search, wander and crawl to finally find your way via often accidental clues. But I also like to get lost now and then in the literal sense of the word. It reminds me of a 2-day trip in the sixth secondary school. The road we took did not lead to our campsite and this caused panic among some classmates. It was getting dark and we would not reach our destination. At that moment, I realised: 'We have our tents with us, it is at least as beautiful here in the middle of the fields, so let's spend the night here'. This may sound like a trivial example, but it shows something of the importance of allowing one's mind to wander. Both during my walks and in my design. Only in this way do you get to places you would otherwise not have seen. And only then does the visual game remain fascinating.

Thanks, Wim. Let's toast to the power of the unexpected: Cheers!

Oh, and here you find the stories behind the all the Yugen designs.

Did you ever wonder … who took the bite? 'The B®ANDIT Logo Sessions'

I like Yugen Kombucha

I like Yugen Kombucha

J'adore Yugen Kombucha

J'adore Yugen Kombucha